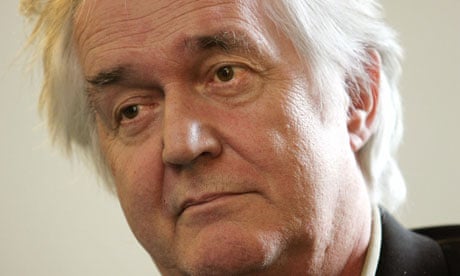

Photograph: Christian Charisius/ Reuters

What is an acceptable shelf life for a fictional detective? Has Wallander gone too soon? Should Henning Mankell have kept him going for a few more years? These are the questions that will trouble fans of Inspector Kurt Wallander, Europe's and arguably the world's most popular policeman, when they finish page 365 of Mankell's latest, and last, novel in the series that began 20 years ago. Wallander is not dead: his creator, though, has made it clear that he will no longer be with us.

There are, according to Mankell's website, 10 books in the series, though other aficionados stretch it to 13 by adding novels in which Wallander is not the central character. Not so many in comparison with other detectives who have a following across the world. Sherlock Holmes kept Arthur Conan Doyle busy for 40 years and 60 stories. Maigret featured in more than 100 cases, if one includes Georges Simenon's short stories as well as more than 70 novels. In the modern era there are writers who know when to call it a day, those who don't, and those who die before their detective does. Walter Mosley and Ian Rankin fall into the first category. Mosley gave Easy Rawlins 11 outings in Los Angeles of the 1950s and 1960s, and no more. "When the 21st century hit, I realised the series no longer spoke to people today," Mosley said. DI Rebus lasted longer in Edinburgh, but Rankin sensibly retired him in 2007.

James Lee Burke, sadly, is a category two man. Detective Dave Robicheaux, despite his wonderful Louisiana backdrop, has been with us far too long – closing in on 20 books – and has become the most self-righteous, self-pitying, guilt-ridden ex-alcoholic in crime fiction. Please, somebody, push him into the bayou, and into the jaws of a man-eating alligator. And do it soon.

Michael Dibdin and Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, even more sadly, fall into category three. They died before their famous detectives, respectively Aurelio Zen in Italy, and Pepe Carvalho in Barcelona, where there is a tourist trail dedicated to the gastronomic ex-communist investigator.

Wallander, too, has made his mark in tourism, drawing visitors to Ystad, the picturesque medieval town in southern Sweden. None has been murdered, which is remarkable in an area awash with serial killers and psychopaths.

There is far more to enjoy in the Wallander series than his solving of crimes, however: his relationships with his father, his daughter Linda, his heavy-drinking ex-wife Mona, his Latvian ex-lover Baiba Liepa, his past, his colleagues, the state. The books would be far less enjoyable without his many difficulties and idiosyncrasies, all of which add to the general sense of Scandinavian gloom that pervades the work of Mankell (son-in-law of Ingmar Bergman) and so many other popular Nordic writers.

One only has to turn to the second page of chapter one of The Troubled Man to find a few lines that are, for fans of Wallander and all good writers of Scandinavian crime, satisfyingly gloomy. Wallander is conscious that, at 60, he is in the "third age". He frequently thinks about death. He recalls that just after his 50th birthday "he had bought a new notebook and tried to record his memories of all the dead people he had come across. It had been a macabre exercise and he had no idea why he had been tempted to pursue it. When he got as far as the 10th suicide, a man in his 40s, a drug addict with more or less every problem it was possible to imagine, he gave up."

There are significant changes to Wallander's life. He becomes a grandfather; he moves from his town-centre apartment in Ystad to a more remote, and more lonely, rural home; and he finds a new companion, a dog.

Of all his colleagues from his first days in Ystad, only one, Martinsson, remains. He, too, is on his way out. When the two men sit and talk over coffee in Wallander's kitchen, Martinsson says, "I just can't take it any more," and starts crying. Wallander, characteristically, offers no physical support as the tears flow, and does not know what to do. He is impressed, though, that Martinsson, who describes his police work as "torture", has the courage to cry in front of another man.

The other grandparents of Linda's daughter are central to the plot. Hakan Von Enke, a retired naval commander, and later his wife, Louise, both disappear. Wallander neglects his duties in Ystad to investigate. He finds himself delving into the past: the cold war, Soviet-Bloc spies, Russian submarines in Swedish waters, and the most famous unsolved crime in Swedish history, the assassination of prime minister Olof Palme in 1986. This gives Wallander, and Mankell, ample opportunity to comment on the social wellbeing, or lack of it, of modern Sweden.

Three actors have played Wallander in different series televised by the BBC, one of them British and two Swedish (annoyingly the least good of the three, Kenneth Branagh, has his picture on the front cover of the book). The detective's popularity is unparalleled, and Mankell has sold more than 30 million books worldwide. He could go on and on. Has he made the right decision to retire the man who made him famous? Yes. Mankell is a category one writer in every respect.

Review thanks to The Guardian

There are, according to Mankell's website, 10 books in the series, though other aficionados stretch it to 13 by adding novels in which Wallander is not the central character. Not so many in comparison with other detectives who have a following across the world. Sherlock Holmes kept Arthur Conan Doyle busy for 40 years and 60 stories. Maigret featured in more than 100 cases, if one includes Georges Simenon's short stories as well as more than 70 novels. In the modern era there are writers who know when to call it a day, those who don't, and those who die before their detective does. Walter Mosley and Ian Rankin fall into the first category. Mosley gave Easy Rawlins 11 outings in Los Angeles of the 1950s and 1960s, and no more. "When the 21st century hit, I realised the series no longer spoke to people today," Mosley said. DI Rebus lasted longer in Edinburgh, but Rankin sensibly retired him in 2007.

James Lee Burke, sadly, is a category two man. Detective Dave Robicheaux, despite his wonderful Louisiana backdrop, has been with us far too long – closing in on 20 books – and has become the most self-righteous, self-pitying, guilt-ridden ex-alcoholic in crime fiction. Please, somebody, push him into the bayou, and into the jaws of a man-eating alligator. And do it soon.

Michael Dibdin and Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, even more sadly, fall into category three. They died before their famous detectives, respectively Aurelio Zen in Italy, and Pepe Carvalho in Barcelona, where there is a tourist trail dedicated to the gastronomic ex-communist investigator.

Wallander, too, has made his mark in tourism, drawing visitors to Ystad, the picturesque medieval town in southern Sweden. None has been murdered, which is remarkable in an area awash with serial killers and psychopaths.

There is far more to enjoy in the Wallander series than his solving of crimes, however: his relationships with his father, his daughter Linda, his heavy-drinking ex-wife Mona, his Latvian ex-lover Baiba Liepa, his past, his colleagues, the state. The books would be far less enjoyable without his many difficulties and idiosyncrasies, all of which add to the general sense of Scandinavian gloom that pervades the work of Mankell (son-in-law of Ingmar Bergman) and so many other popular Nordic writers.

One only has to turn to the second page of chapter one of The Troubled Man to find a few lines that are, for fans of Wallander and all good writers of Scandinavian crime, satisfyingly gloomy. Wallander is conscious that, at 60, he is in the "third age". He frequently thinks about death. He recalls that just after his 50th birthday "he had bought a new notebook and tried to record his memories of all the dead people he had come across. It had been a macabre exercise and he had no idea why he had been tempted to pursue it. When he got as far as the 10th suicide, a man in his 40s, a drug addict with more or less every problem it was possible to imagine, he gave up."

There are significant changes to Wallander's life. He becomes a grandfather; he moves from his town-centre apartment in Ystad to a more remote, and more lonely, rural home; and he finds a new companion, a dog.

Of all his colleagues from his first days in Ystad, only one, Martinsson, remains. He, too, is on his way out. When the two men sit and talk over coffee in Wallander's kitchen, Martinsson says, "I just can't take it any more," and starts crying. Wallander, characteristically, offers no physical support as the tears flow, and does not know what to do. He is impressed, though, that Martinsson, who describes his police work as "torture", has the courage to cry in front of another man.

The other grandparents of Linda's daughter are central to the plot. Hakan Von Enke, a retired naval commander, and later his wife, Louise, both disappear. Wallander neglects his duties in Ystad to investigate. He finds himself delving into the past: the cold war, Soviet-Bloc spies, Russian submarines in Swedish waters, and the most famous unsolved crime in Swedish history, the assassination of prime minister Olof Palme in 1986. This gives Wallander, and Mankell, ample opportunity to comment on the social wellbeing, or lack of it, of modern Sweden.

Three actors have played Wallander in different series televised by the BBC, one of them British and two Swedish (annoyingly the least good of the three, Kenneth Branagh, has his picture on the front cover of the book). The detective's popularity is unparalleled, and Mankell has sold more than 30 million books worldwide. He could go on and on. Has he made the right decision to retire the man who made him famous? Yes. Mankell is a category one writer in every respect.

Review thanks to The Guardian